January 7.

St. Lucian. St. Cedd. St. Kentigerna. St. Aldric. St. Thillo. St. Canut.

St. Lucian.

This saint is in the calendar of the church of England on the following day, 8th of January. He was a learned Syrian. According to Butler, he corrected the Hebrew version of the Scriptures for the inhabitants of Palestine, during some years was separated from the Romish church, afterwards conformed to it, and died after nine years imprisonment, either by famine or the sword, on this day, in the year 312. It further appears from Butler, that the Arians affirmed of St. Lucian, that to him Arius was indebted for his distinguishing doctrine, which Butler however denies.

ST. DISTAFF'S DAY, OR ROCK-DAY.

The day after Twelfth-day was so called because it was celebrated in honour of the rock, which is a distaff held in the hand, from whence wool is spun by twirling a ball below. It seems that the burning of the flax and tow belonging to the women, was the men's diversion in the evening of the first day of labour after the twelve days of Christmas, and that the women repaid the interruption to their industry by sluicing the mischief-makers. Herrick tells us of the custom in his Hesperides:—

St. Distaff's day, or the morrow after Twelfth-day.

Partly work, and partly play,

Ye must on S. Distaff's day:

From the plough soone free your teame,

Then come home and fother them.

If the maides a spinning goe,

Burne the flax, and fire the tow;

* * *

Bring in pailes of water then,

Let the maides bewash the men:

Give S. Distaffe all the right,

Then bid Christmas sport good-night.

And next morrow, every one

To his own vocation.In elder times, when boisterous diversions were better suited to the simplicity of rustic life than to the comparative refinement of our own, this contest between fire and water must have afforded great amusement.

CHRONOLOGY.

1772. "An authentic, candid, and circumstancial narrative of the astonishing transactions at Stockwell, in the county of Surrey, on Monday and Tuesday, the 6th and 7th days of January, 1772, containing a series of the most surprising and unaccountable events that ever happened; which continued from first to last upwards of twenty hours, and at different places. Published with the consent and approbation of the family, and other parties concerned, to authenticate which, the original Copy is signed by them."

This is the title of an octavo tract published in "London, printed for J. Marks, bookseller, in St. Martin's-lane, 1772." It describes Mrs. Golding, an elderly lady, at Stockwell, in whose house the transactions happened, as a woman of unblemished honour and character; her niece, Mrs. Pain, as the wife of a farmer at Brixton-causeway, the mother of several children, and well known and respected in the parish; Mary Martin as an elderly woman, servant to Mr. and Mrs. Pain, with whom she had lived two years, having previously lived four years with Mrs. Golding, from whom she went into Mrs. Pain's service; and Richard Fowler and Sarah, his wife, as an honest, industrious, and sober couple, who lived about opposite to Mr. Pain, and the Brick-pound. These were the subscribing witnesses to many of the surprising transactions, which were likewise witnessed by some others. Another person who bore a principal part in these scenes was Ann Robinson, aged about twenty years, who had lived servant with Mrs. Golding but one week and three days. The "astonishing transactions" in Mrs. Golding's house were these:

On Twelfth-day 1772, about ten o'clock in the forenoon, as Mrs. Golding was in her parlour, she heard the china and glasses in the back kitchen tumble down and break; her maid came to her and told her the stone plates were falling from the shelf; Mrs. Golding went into the kitchen and saw them broke. Presently after, a row of plates from the next shelf fell down likewise, while she was there, and nobody near them; this astonished her much, and while she was thinking about it, other things in different places began to tumble about, some of them breaking, attended with violent noises all over the house; a clock tumbled down and the case broke; a lantern tht hung on the staircase was thrown down and the glass broke to pieces; an earthen pan of salted beef broke to pieces and the beef fell about; all this increased her surprise, and brought several persons about her, among whom was Mr. Rowlidge, a carpenter, who gave it as his opinion that the foundation was giving way and that the house was tumbling down, occasioned by the too great weight of an additional room erected above: "so ready," says the narrative, "are we to discover natural causes for every thing."

Mrs. Golding ran into Mr. Gresham's house, next door to her, where she fainted, and in the interim, Mr. Rowlidge, and other persons, were removing Mrs. Golding's effects from her house, for fear of the consequences prognosticated. At this time all was quiet; Mrs. Golding's maid remaining in her house, was gone up stairs, and when called upon several times to come down, for fear of the dangerous situation she was thought to be in, she answered very coolly, and after some time came down deliberately, without any seeming fearful apprehensions.

Mrs. Pain was sent for from Brixton-causeway, and desired to come directly, as her aunt was supposed to be dead;—this was the message to her. When Mrs. Pain came, Mrs. Golding was come to herself, but very faint from terror.

Among the persons who were present, was Mr. Gardner, a surgeon, of Clapham, whom Mrs. Pain desired to bleed her aunt, which he did; Mrs. Pain asked him if the blood should be thrown away; he deisred it might not, as he would examine it when cold. These minute particulars would not be taken notice of, but as a chain to what follows. For the next circumstance is of a more astonishing nature than any thing that had preceded it; the blood that was just congealed, sprung out of the basin upon the floor, and presently after the basin broke to pieces; this china basin was the only thing broke belonging to Mr. Gresham; a bottle of rum that stood by it broke at the same time.

Among the things that were removed to Mr. Gresham's was a tray full of china, &c. a japan bread-basket, some mahogany waiters, with some bottles of liquors, jars of pickles, &c. and a pier glass, which was taken down by Mr. Saville, (a neighbour of Mrs. Golding's;) he gave it to one Robert Hames, who laid it on the grass-plat at Mr. Gresham's; but before he could put it out of his hands, some parts of the frame on each side flew off; it raining at that time, Mrs. Golding desired it might be brought into the parlour, where it was put under a side-board, and a dressing-glass along with it; it had not been there long before the glasses and china which stood on the side-board, began to tumble about and fall down, and broke both the glasses to pieces. Mr. Saville and others being asked to drink a glass of wine or rum, both the bottles broke in pieces before they were uncorked.

Mrs. Golding's surprise and fear increasing, she did not know what to do or where to go; wherever she and her maid were, these strange, destructive circumstances followed her, and how to help or free herself from them, was not in her power or any other person's present: her mind was one confused chaos, lost to herself and every thing about her, drove from her own home, and afraid there would be none other to receive her, she at last left Mr. Gresham's, and went to Mr. Mayling's, a gentleman at the next door, here she staid about three quarters of an hour, during which time nothing happened. Her maid staid at Mr. Gresham's, to help put up what few things remained unbroken of her mistress's, in a back apartment, when a jar of pickles that stood upon a table, turned upside down, then a jar of raspberry jam broke to pieces.

Mrs. Pain, not choosing her aunt should stay too long at Mr. Mayling's, for fear of being troublesome, persuaded her to go to her house at Rush Common, near Brixton-causeway, where she would endeavour to make her as happy as she could, hoping by this time all was over; as nothing had happened at that gentleman's house while she was there. This was about two o'clock in the afternoon.

Mr. and Mrs. Gresham were at Mr. Pain's house, when Mrs. Pain, Mrs. Golding, and her maid went there. It being about dinner time they all dined together; in the interim Mrs. Golding's servant was sent to her house to see how things remained. When she returned, she told them nothing had happened since they left it. Sometime after Mr. and Miss Gresham went home, every thing remaining quiet at Mr. Pain's: but about eight o'clock in the evening a fresh scene began; the first thing that happened was, a whole row of pewter dishes except one, fell from off a shelf to the middle of the floor, rolled about a little while, then settled, and as soon as they were quiet, turned upside down; they were then put on the dresser, and went through the same a second time: next fell a whole row of pewter plates from off the second shelf over the dresser to the ground, and being taken up and put on the dresser one in another, they were thrown down again. Two eggs were upon one of the pewter shelves, one of them flew off, crossed the kitchen, and struck a cat on the head, and then broke in pieces.

Next Mary Martin, Mrs. Pain's servant, went to stir the kitchen fire, she got to the right hand side of it, being a large chimney as is usual in farm houses, a pestle and mortar that stood nearer the left hand end of the chimney shelf, jumped about six feet on the floor. Then went candlesticks and other brasses: scarce any thing remaining in its place. After this the glasses and china were put down on the floor for fear of undergoing the same fate.

A glass tumbler that was put on the floor jumped about two feet and then broke. Another that stood by it jumped about at the same time, but did not break till some hours after, when it jumped again and then broke. A china bowl that stood in the parlour jumped from the floor, to behind a table that stood there. This was most astonishing, as the distance from where it stood was between seven and eight feet, but was not broke. It was put back by Richard Fowler, to its place, where it remained some time, and then flew to pieces.

The next thing that jumped was a mustard-pot, that jumped out of a closet and was broke. A single cup that stood upon the table (almost the only thing remaining) jumped up, flew across the kitchen, ringing like a bell, and then was dashed to pieces against the dresser. A tumbler with run and water in it, that stood upon a wiater upon a table in the parlour, jumped about ten feet and was broke. The table then fell down, and along with it a selver tankard belonging to Mrs. Golding, the waiter in which had stood the tumbler, and a candlestick. A case bottle then flew to pieces.

The next circumstance was, a ham, that hung on one side of the kitchen chimney, raised itself from the hook and fell down to the ground. Some time after, another ham, that hung on the other side of the chimney, likewise underwent the same fate. Then a flitch of bacon, which hung up in the same chimney, fell down.

All the family were eye-witnesses to these circumstances as well as other persons, some of whom were so alarmed and shocked, that they could not bear to stay.

At the times of the action, Mrs. Golding's servant was walking backwards and forwards, either in the kitchen or parlour, or wherever some of the family happened to be. Nor could they get her to sit down five minutes together, except at one time for about half an hour towards the morning, when the family were at prayers in the parlour; then all was quiet; but, in the midst of the greatest confusion, she was as much composed as at any other time, and with uncommon coolness of temper advised her mistress not to be alarmed or uneasy, as she said these things could not be helped.

"This advice," it is observed in the narrative, surprised and startled her mistress, almost as much as the circumstances that occasioned it. "For how can we suppose," says the narrator, "that a girl of about twenty years old, (an age when female timidity is too often assisted by superstition,) could remain in the midst of such calamitous circumstances, (except they proceeded from causes best known to herself,) and not be struck with the same terror as every other person was who was present. These reflections led Mr. Pain, and at the end of the transactions, likewise Mrs. Golding, to think that she was not altogether so unconcerned as she appeared to be."

About ten o'clock at night, they sent over the way to Richard Fowler, to desire he would come and stay with them. He came and continued till one in the morning, when he was so terrified, that he could remain no longer.

As Mrs. Golding could not be persuaded to go to bed, Mrs. Pain, at one o'clock, made an excuse to go up stairs to her youngest child, under pretence of getting it to sleep; but she really acknowledged it was through fear, as she declared she could not sit up to see such strange things going on, as every thing one after another was broken, till there was not above two or three cups and saucers remaining out of a considerable quantity of china, &c. which was destroyed to the amount of some pounds.

About five o'clock on Tuesday morning, the 7th, Mrs. Golding went up to her niece, and desired her to get up, as the noises and destructions were so great she could continue in the house no longer. Mrs. Golding and her maid went over the way to Richard Fowler's: when Mrs. Golding's maid had seen her safe to Richard Fowler's, she came back to Mrs. Pain, to help her to dress the children in the barn, where she had carried them for fear of the house falling. At this time all was quiet: they then went to Fowler's, and then began the same scene as had happened at the other places. All was quiet here as well as elsewhere, till the maid returned.

When they got to Mr. Fowler's, he began to light a fire in his back room. When done, he put the candle and candlestick upon a table in the fore room. This apartment Mrs. Golding and her maid had passed through. Another candlestick with a tin lamp in it that stood by it, were both dashed together, and fell to the ground. At last the basket of coals tumbled over, and the coals rolling about the room, the maid desired Richard Fowler not to let her mistress remain there, as she said, wherever she was, the same things would follow. In consquence of this advice, and fearing greater losses to himself, he desired Mrs. Golding would quit his house; but first begged her to consider within herself, for her own and the public sake, whether or not she had not been guilty of some atrocious crime, for which Providence was determined to pursue her on this side [of] the grave. Mrs. Golding told him she would not stay in his house, or any other person's, as her conscience was quite clear, and she could as well wait the will of Providence in her own house as in any other place whatever; upon which she and her maid went home, and Mrs. Pain went with them.

After they had got to Mrs. Golding's, a pail of water, that stood on the floor, boiled like a pot; a box of candles fell from a shelf in the kitchen to the floor, and they rolled out, but none were broken, and the table in the parlour fell over.

Mr. Pain then desired Mrs. Golding to send her maid for his wife to come to them, and when she was gone all was quiet; upon her return she was immediately discharged, and no disturbances happened afterwards; this was between six and seven o'clock on Tuesday morning. At Mrs. Golding's were broken the quantity of three pails full of glass, china, &c. Mrs. Pain's filled two pails.

The accounts here related are in the words of the "narrative," which bears the attestation of the witnesses before mentioned. The affair is still remembered by many persons: it is usually denominated the "Stockwell Ghost," and deemed inexplicable. It must be recollected, however, that the mysterious movements were never made but when Ann Robinson, Mrs. Golding's maid-servant, was present, and that they wholly ceased when she was dismissed. Though these two circumstances tend to prove that the girl was the cause of the disturbances, scarcely any one who lived at that time listened patiently to the presumption, or without attributing the whole to witchcraft. One lady, whom the editor of the Every-Day Book conversed with several times on the subject, firmly believed in the witchcraft, because she had been eye-witness to the animation of the inanimate crockery and furniture, which she said could not have been effected by human means—it was impossible. He derived, however, a solution of these "impossibilities" from the late Mr. J. B———, at his residence in Southampton-street, Camberwell, towards the close of the year 1817. Mr. B——— said, all London was in an uproar about the "Stockwell Ghost" for a long time, and it would have made more noise that the "Cock-lane Ghost," if it had lasted longer; but attention to it gradually died away, and most people believed it was supernatural. Mr. B———, in continuation, observed, that some years after it happened, he became acquainted with this very Ann Robinson, without knowing for a long time that she had been the servant-maid to Mrs. Golding. He learned it by accident, and told her what he had heard. She admitted it was true, and in due season, he says, he got all the story out. She had fixed long horse hairs to some of the crockery, and put wires under others; on pulling these, the "movables" of course fell. Mrs. Golding was terribly frightened, and so were all who saw any thing tumble. Ann Robinson herself, dexterously threw many of the things down, which the persons present, when they turned round and saw them in motion or broken, attributed to unseen agency. These spectators were all too much alarmed by their own dread of infernal power to examine any thing. They kept at an awful distance, and sometimes would not look at the utensils, lest they might face fresh horrors; of these tempting opportunities she availed herself. She put the eggs in motion, and after one only fell down, threw the other at the cat. Their terrors at the time, and their subsequent conversations magnified many of the circumstances beyond the facts. She took advantage of absences to loosen the hams and bacon, and attach them by the skins; in short, she effected all the mischief. She caused the water in the pail to appear as if it boiled by slipping in a paper of chemical powders as she passed, and afterwards it bubbled. "Indeed," said Mr. B———, "there was a love story connected with the case, and when I have time, I will write out the whole, as I got it by degrees from the woman herself. When she saw the effect of her first feats, she was tempted to exercise the dexterity beyond her original purpose for mere amusement. She was astonished at the astonishment she caused, and so went on from one thing to another; and being quick in her motions and shrewd, she puzzled all the simple old people, and nearly frightened them to death." Mr. B——— chuckled mightily over his recollections; he was fond of a practical joke, and enjoyed the tricks of Ann Robinson with all his heart. By his acuteness, curiosity, and love of drollery, he drew from her the entire confession; and "as the matter was all over years ago, and no more harm could be done," said Mr. B., "I never talked about it much, for her sake; but of this I can assure you, that the only magic in the thing was, her dexterity and the people's simplicity." Mr. B. promised to put down the whole on paper; but he was ailing and infirm, and accident prevented the writer from caring much for a "full, true, and particular account," which he could have had at any time, till Mr. Brayfield's death rendered it unattainable.

THE SEASON.

Mr. Arthur Aikin, in his "Calendar of Nature," presents us with a variety of acceptable information concerning the operations of nature throughout the year. "The plants at this season," he says, "are provided by nature with a sort of winter-quarters, which secure them from the effects of cold. Those called herbaceous, which die down to the root every autumn, are now safely concealed under-ground, preparing their new shoots to burst forth when the earth is softened in spring. Shrubs and trees, which are exposed to the open air, have all their soft and tender parts closely wrapt up in buds, which by their firmness resist all the power of frost; the larger kinds of buds, and those which are almost ready to expand, are further guarded by a covering of resin or gum, such as the horse-chestnut, the sycamore, and the lime. Their external covering, however, and the closeness of their internal texture, are of themselves by no means adequate to resist the intense cold of a winter's night: a bud detached from its stem, enclosed in glass, and thus protected from all access of external air, if suspended from a tree during a sharp frost, will be entirley penetrated, and its parts deranged by the cold, while the buds on the same tree will not have sustained the slightest injury; we just therefore attribute to the living principle in vegetables, as well as animals, the power of resisting cold to a very considerable degree: in animals, we know, this power is generated from the decomposition of air by means of the lungs, and disengagement of heat; how vegetables acquire this property remains for future observations to discover. If one of these buds be carefully opened, it is found to consist of young leaves rolled together, within which are even all the blossoms in miniature that are afterwards to adorn the spring."

During the mild weather of winter, slugs are in constant motion preying on plants and green wheat. Their coverings of slime prevent the escape of animal heat. and hence they are enabled to ravage when their bretheren of the shell, who are more sensible of cold, lie dormant. Earth-worms likewise appear about this time; but let the man of nice order, with a little garden, discriminate between the destroyer, and the innocent and useful inhabitant. One summer evening, the worms from beneath a small grass plat, lay half out of their holes, or were dragging "their slow length" upon the surface. They were all carefully taken up, and preserved as a breakfast for the ducks. In the following year, the grass-plat, which had flourished annually with its worms, vegetated unwillingly. They were the under-gardeners that loosened the sub-soil, and let the warm air through their entrances to nourish the roots of the herbage.

"Their calm desires that asked but little room,"

were unheeded, and their usefulness was unknown, until their absence was felt.

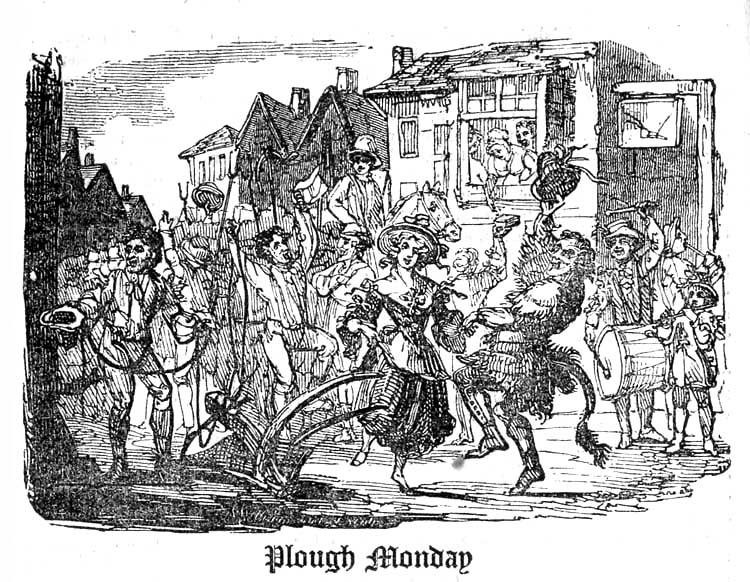

Plough Monday

The first Monday after Twefth-day is called Plough Monday, and appears to have received that name because it was the first day after Christmas that husbandmen resumed the plough. In some parts of the country, and especially in the north, they draw the plough in procession to the doors of the villagers and townspeople. Long ropes are attached to it, and thirty or forty men, stripped to their clean white shirts, but protected from the weather by waistcoats beneath, drag it along. Their arms and shoulders are decorated with gay-coloured ribbons, tied in large knots and bows, and their hats are smartened in the same way. They are usually accompanied by an old woman, or a boy dressed up to represent one; she is gaily bedizened, and called Bessy. Sometimes the sport is assisted by a humorous countryman to represent a fool. He is covered with ribbons, and attired in skins, with a depending tail, and carries a box to collect money from the spectators. They are attended by music, and Morris-dancers when they can be got; but there is always a sportive dance with a few lasses in all their finery, and a superabundance of ribbons. When this merriment is well managed, it is very pleasing. The money collected is spent at night in conviviality. At must not be supposed, however, that in these times, the twelve days of Christmas are devoted to pastime, although the custom remains. Formerly, indeed, little was done in the field at this season, and according to "Tusser Redivivus," during the Christmas holidays, gentlemen feasted the farmers, and every farmer feasted his servants and taskmen. Then Plough Monday reminded them of their business, and on the morning of that day, the men and maids strove who should show their readiness to commence the labours of the year, by rising the earliest. If the ploughman could get his whip, his plough-staff, hatchet, or any field implement, by the fireside, before the maid could get her kettle on, she lost her Shrove-tide cock to the men. Thus did our forefather strive to allure youth to their duty, and provided them innocent mirth as well as labour. On Plough Monday night the farmer gave them a good supper and strong ale. In some places, where the ploughman went to work on Plough Monday, if, on his return at night, he came with his whip to the kitchen-hatch, and cried "Cock in pot," before the maid could cry "Cock on the dunghill," he gained a cock for Shrove Tuesday.

Blomefield's History of Norfolk tends to clear the origin of the annual processions on Plough Monday. Anciently, a light called the Plough-light, was maintained by old and young persons who were husbandmen, before images in some churches, and on Plough Monday they had a feast, and went about with a plough and dancers to get money to support the Plough-light. The Reformation put out these lights; but the practice of going about with the plough begging for money remains, and the "money for light" increases the income of the village alehouse. Let the sons of toil make glad their hearts with "Barley-wine;" let them also remember to "be merry and wise." Their old acquaintance, "Sir John Barleycorn," has had heavy complaints agianst him. There is "The Arraigning and Indicting of SIR JOHN BARLEYCORN, knt. printed for Timothy Tosspot." This whimsical little tract describes him as of "noble blood, well beloved in England, a great support to the crown, and a maintainer of both rich and poor." It formally places him upon his trial, at the sign of the Three Loggerheads, before "Oliver and Old Nick his holy father," as judges. The witnesses for the prosecution were cited under the hands and seals of the said judges, sitting "at the sign of the Three merry Companions in Bedlam; that is to say, Poor Robin, Merry Tom, and Jack Lackwit." At the trial, the prisoner, sir John Barleycorn, pleaded not guilty.

Lawyer Noisy.— May it please your lordship, and gentlemen of the jury, I am counsel for the king against the prisoner at the bar, who stands indicted of many heinous and wicked crimes, in that the said prisoner, with malice propense and several wicked ways, has conspiered and brought about the death of several of his majesty's loving sobjects, to the great loss of several poor families, who by this means have been brought to ruin and beggary, which, before the wicked designs and contrivances of the prisoner, lived in a flourishing and reputable way, but now are reduced to low circumstances and great misery, to the great loss of their own families and the nation in general. We shall call our evidence; and if we make the facts appear, I do not doubt but you will find him guilty, and your lordships will award such punishment as the nature of his crimes deserve.

Vulcan, the Blacksmith.— My lords, sir John has been a great enemy to me, and many of my friends. Many a time, when I have been busy at my work, not thinking any harm to any man, having a fire-spark in my throat, I, going over to the sign of the Cup and Can for one pennyworth of ale, there I found sir John, and thinking no hurt to any man, civilly sat me down to spend my twopence; but in the end, sir John began to pick a quarrel with me. Then I started up, thinking to go away; but sir John had got me by the top of the head, that I had no power to help myself, and so by his strength and power he threw me down, broke my head, my face, and almost all my bones, that I was not able to work for three days; nay, more than this, he picked my purse, and left me never a penny, so that I had not wherewithal to support my family, and my head ached to such a degree, that I was not able to work for three or four days; and this set my wife a scolding, so that I not only lost the good opinion my neighbours had of me, but likewise raised such a storm in my family, that I was forced to call in the parson of the parish to quiet the raging of my wife's temper.

Will, the Weaver.— I am but a poor man, and have a wife and a charge of children: yet this knowing sir John will never let me alone; he is always enticing me from my work, and will not be quiet till he hath got me to the alehouse; and then he quarrels with me, and abuses me most basely; and sometimes he binds me hand and foot, and throws me in the ditch, and there stays with me all night, and next morning leaves me but one penny in my pocket. About a week ago, we had not been together above an hour, before he began to give me cross words: at our first meeting, he seemed to have a pleasant countenance, and often smiled in my face, and would make me sing a merry catch or two; but in a little time, he grew very churlish, and kicked up my heels, set my head where my heels should be, and put my shoulder out, so that I have not been able to use my shuttle ever since, which has been a great detriment to my family, and great misery to myself.

Stitch, the Tailor, deposed to the same effect.

Mr. Wheatly.— The inconveniencies I have received from the prisoner are without number, and the trouble he occasions in the neighbourhood is not to be expressed. I am sure I have been oftentimes very highly esteemed both with lords, knights, and squires, and none could please them so well as James Wheatly, the baker; but now the case is altered; sir John Barleycorn is the man that is highly esteemed in every place. I am now but poor James Wheatly, and he is sir John Barleycorn at every word; and that word hath undone many an honest man in England; for I can prove it to be true, that he has caused many an honest man to waste and consume all that he hath.

The prisoner, sir John Barleycorn, being called on for his defence, urged, that to his accusers he was a friend, until they abused him; and said, if any one is to be blamed, it is my brother Malt. My brother is now in court, and if your lordships please, may be examined to all those facts which are now laid to my charge.

Court.— Call Mr. Malt.

Malt appears.

Court.— Mr. Malt, you have (as you have been in court) heard the indictment that is laid against your brother, sir John Barleycorn, who says, if any one ought to be accused, it should be you; but as sir John and you are so nearly related to each other, and have lived so long together, the court is of opinion he cannot be acquitted, unless you can likewise prove yourself innocent of the crimes which are laid to his charge.

Malt.— My lords, I thank you for the liberty you now indulge me with, and think it a great happiness, since I am so strongly accused, that I have such learned judges to determine these complaints. As for my part, I will put the matter to the bench. First, I pray you consider with yourselves, all tradesmen would live; and although Master Malt does make sometimes a cup of good liquor, and many men come to taste it, yet the fault is neither in me nor my brother John, but in such as those who make this complaint against us, as I shall make it appear to you all.

In the first place, which of you all can say but Master Malt can make a cup of good liquor, with the help of a good brewer; and when it is made, it will be sold. I pray which of you all can live without it? But when such as these, who complain of us, find it to be good, then they have such a greedy mind, that they think they never have enough, and this overcharge brings on the inconveniences complained of, makes them quarrelsome with one another, and abusive to their very friends, so that we are forced to lay them down to sleep. From hence it ap pears it is from their own greedy desires all these troubles arise, and not from wicked designs of our own.

Court.— Truly, we cannot see that you are in the fault. Sir John Barleycorn, we will show you so much favour, that if you can bring any person of reputation to speak to your character, the court is disposed to acquit you. Bring in your evidence, and let us hear what they can say in your behalf.

Thomas, the Ploughman.— May I be allowed to speak my thoughts freely, since I shall offer nothing but the truth.[?]

Court.— Yes, thou mayest be bold to speak the truth, and no more, for that is the cause we sit here for; therefore speak boldly, that we may understand thee.

Ploughman.— Gentlemen, sir John is of an ancient house, and is come of a noble race; there is neither lord, knight, nor squire, but they love his company, and he theirs; as long as they don't abuse him, he will abuse no man, but doth a great deal of good. In the first place, few ploughmen can live without him; for if it were not for him, we should not pay our landlords their rent; and then what would such men as you do for money and clothes? Nay, your gay ladies would care but little for you, if you had not your rents coming in to maintain them; and we could never pay, but that sir John Barleycorn feeds us with money; and yet would you seek to take away his life! For shame, let your malice cease, and pardon his life, or else we are all undone.

Bunch, the Brewer.— Gentlemen, I beseech you hear me. My name is Bunch, a brewer; and I believe few of you can live without a cup of good liquor, no more than I can without the help of sir John Barleycorn. As for my own part, I maintain a great charge, and keep a great many men at work; I pay taxes forty pounds a year to his majesty, God bless him, and all this is maintained by the help of sir John; then how can any man for shame seek to take away his life.

Mistress Hostess.— To give evidence in behalf of sir John Barleycorn, gives me pleasure, since I have an opportunity of doing justice to so honourable a person. Through him the administration receives large supplies; he likewise greatly supports the labourer, and enlivens the conversation. What pleasure could there be at a sheep-clipping without his company, or what joy at a feast without his assistance? I know him to be an honest man, and he never abused any man, if they abused not him. If you put him to death, all England is undone, for there is not another in the land can do as he can do, and hath done; for he can make a cripple go, the coward fight, and a soldier neither feel hunger nor cold. I beseech you, gentlemen, let him live, or else we are all undone; the nation likewise will be distressed, the labourer impoverished, and the husbandman ruined.

Court.— Gentlemen of the jury, you have now heard what has been offered against sir John Barleycorn, and the evidence that has been produced in his defence. If you are of opinion he is guilty of those wicked crimes laid to his charge, and has with malice propense conspired with brought about the death of several of his majesty's loving subjects, you are then to find him guilty; but if, on the contrary, you are of the opinion that he had no real intention of wickedness, and was not the immediate, but only the accidental, cause of these evils laid to his charge, then, according to the statute law of this kingdom, you ought to acquit him.

Verdict, NOT GUILTY.

From this facetious little narrative may be learned the folly of excess, and the injustice of charging a cheering beverage, with the evil consequences of a man taking a cup more of it that will do him good.